Notes

20 Years of Ebola, and How Photography Has Changed

Monrovia, Liberia, 2014

Uganda, 2000

With all the visual focus on Ebola, a photography writer asked me the other day how the news photos of the outbreak this year compared with those from the past two decades. What follows is more of a quick excursion than a grand tour. I should add, though, that the exercise, compelling enough in relation to illness and Africa, was particularly interesting in observing how news photos have changed. Another thing to emphasize — because the media and the public aren’t always mindful of history, especially when hysteria comes into play — is that Ebola isn’t either new or unusual. As mic.com pointed out recently, “there have been at least 33 outbreaks of Ebola since its discovery in 1976” and “on average, an outbreak of the actual Ebola virus occurs nearly every year.”

1. Art vs information

The first thing I observed — reflected in the pair above — is how much today’s news photo, most of them digital, have become more artful and more abstract, more dramatic and more theatrical. (The first one was taken by John Moore in Liberia on October 10th and the other, by Jodi Bieber, is from a World Press prize-winning set from Uganda taken in 2000.)

I guess we could say that the artistry can either complement or compete with and overshadow the photo’s factual, or information value. Both the Moore and Bieber photo are about the removal of a body, but the visual language in Moore’s picture takes the liberty of adding more poetry and spiritual symbolism, as if the corpse is ascending to the sky. Whereas the thatched roofs in Bieber’s shot are more utilitarian and descriptive of person and place, Moore’s photo (though you can see buildings on the side) is less interested in physical context. (Can we be so bold as to say this is true of most news photos today?) Clearly, Moore’s shot is more about the darkness and the emotional balance in that cloud, the silvery effect of the light on the white suits and the way that orange plastic pops and the light shimmers off of it.

2. Portraiture

Central Liberia, October, 2014

Zaire, May 1995

It’s interesting looking at this pairing in the Facebook and the selfie age. Examining the historical Getty, Corbis and World Press edits I drew most heavily on, there were a good share of portraits but they seemed decidedly different than the current standard. Simply put, there was a more singular focus on the individual’s function or role. The contemporary portraits, on the other hand, seem to place more focus on the subject’s personality.

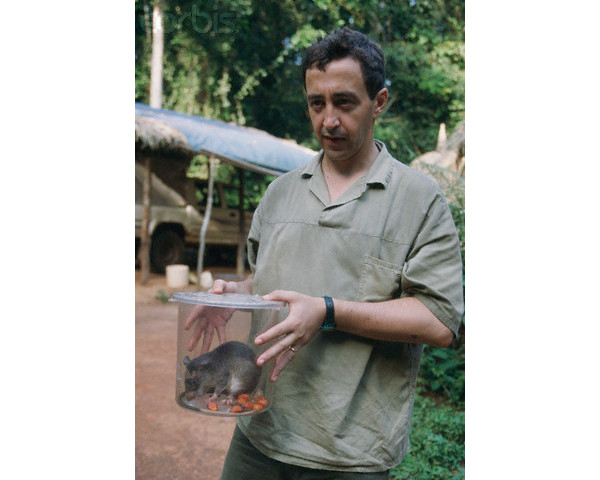

You can see that especially in this portrait by Patrick Robert for Corbis where the subject is photographed for his role as an Ebola researcher conducting experiments on animals. His function and activity is so central, he’s not even looking in the camera. (If you’re thinking this is arbitrary, the lack of eye contact is reflected also in Robert’s shot above and the other portraits in the edit.)

Ivory Coast, 1996

(Seems Warhol was spot on about everyone’s 15 minutes.) As a far cry from both of Patrick’s comparatively unsexy photos, Moore’s Navy microbiologist plays to the camera, his knowing expression and his touting of the vial brings a personal “cool factor” to the preparation of blood samples, an otherwise perfunctory task.

3. Color, Culture and Power. (Or, What’s in a Suit?)

Zaire, May 14, 1995

Ten or twenty years ago, health workers didn’t have the masks and the technological suits they do today. In general, there were more photos that showed people’s skin. This may sound ridiculous, but I’ve had the opportunity over the last month or two to talk to quite a few people about this, and the pervasive whiteness of these high tech suits seems to have a telling, if unintended effect. Even if, looking around the edges of the suit, you see the health worker is black, it still reads to viewers like the responders are white, creating the sense of whites and the west coming to the rescue.

Monrovia, Liberia. August 2014

This photo by John Moore that circulated widely in August is a powerful example. In the way in which the Liberians are relegated to the background, and to the shadow, the abstraction yields a consideration of whiteness as a symbol of power and authority. If it seems to overwhelm the dialogue here, what’s also significant is how much other photographs play the theme even more strongly (though partly in an ironic way?), elevating the theme of black-and-white and the dynamic between the lighter-skinned people and the dark continent to increasing levels of both emphasis and abstraction.

Liberia, September 2014

Case in point, we have this image by Benedicte Kurzen, the patient’s face almost too dark to be distinguishable. Of course, the symbolism here is just as much about life and death as race and technology, the Red Cross worker looking almost like a ghost.

Monrovia, Liberia. August 2014

Finally, this photo by Kieran Kesner seems to push the contrast to its limits, the whole story reduced to a reading of black-and-white.

4. Formality vs. Informality. Reporting vs. Storytelling/Picture Painting

Monrovia, October 2014

Uganda, 2000

Looking at Ebola images a decade or so back suggests how news photos were stiffer, more formal, less intimate. In another photo from Jodi Bieber’s World Press award edit published in 2000 in The New York Times Magazine, the photo of the mother handing over her baby to the aid workers, candid or not (and ultra-cautious or not), seems awkward in the same way early snapshots seemed more awkward or self-conscious. Today, images are more dramatic and “storyful” than they are formal or static. Compare Bieber’s photo to still another John Moore photo, part of an edit in which a health worker walks a baby, mother and grandmother, all with fevers, to a holding center in the West Port neighborhood of Monrovia.

In contrast to the realm of print, I’m also wondering if today’s online journalism, and specifically the prevalence of the photo gallery, is part of the reason why news photos can be both more evocative and more “episodic,” whereas historically one photo had to tell the whole story. (Here, by the way, is the 19 photo sequence at Zimbio that encompasses the story of this family, including Benson, the 2 month-old, being taken to the holding center.)

5. Intimacy

Sept, 2014. Monrovia, Liberia

Angola, 2005

It seems photojournalism today seeks to much more intentionally stir strong feelings and emotions. In so many instances, however, one has to ask how much the emotion ups our knowledge and and information value versus how much its stimulation, eliciting feelings like sadness, concern or pity at the expense of a more humanistic and insightful view. Take the image above by Glenna Gordon of the health care workers holding hands and praying before entering an isolation ward. The photo below it, taken in 2005 in Angola by AFP photographer Florence Panoussian displays camaraderie, for sure. Gordon’s photo, in contrast however, is a duet of feeling and information viscerally illustrating the intensity, the horrific tragedy and the suffering and loss that these aid workers endure.

6. Fate

Uganda, 2000

Finally, this Bieber photo also traffics in the symbolism of the stricken African and the white westerner as the benefactor or savior. There is more practical theme in play here, however, particularly relevant to the Ebola coverage in the past and the imagery now.

October 2014, Bong Country, Liberia

In the past, as reflected in Bieber’s photo from 2000, the disease was an absolute death sentence. In Daniel Berehulak’s photo for the NY Times, however, whether this man who walks out of a “confirmed ward” in Liberia simply fell prey to a false positive lab test or treatment made the difference, what we’re seeing in some number of images (primarily in the States, of course, as the result of new therapies) is that some people are getting out alive.

(photo 1: John Moore/Getty Images caption: An Ebola burial team loads the body of a woman, 54, onto a truck for cremation in the New Kru Town suburb on October 10, 2014 of Monrovia, Liberia. The World Health Organization says the Ebola epidemic has now killed more than 4,000 people in West Africa.photo 2: Jodi Bieber for The New York Times Magazine – World Press 2000 – Magazine Category: People in the News stories 3rd prize caption: Uganda: An outbreak of the Ebola virus: Ambulance workers have to wear protective clothing and dare not touch victims. Their job is to transport the sick and bury the dead. The virus causes massive hemorrhaging, and is highly infectious. There is no cure, and it kills around half the people infected. photo 3: John Moore/Getty Images caption: U.S. Navy microbiologist Lt. Jimmy Regeimbal prepares to test blood samples for Ebola at the U.S. Navy mobile laboratory of on October 7, 2014 near Gbarnga in Bong County of central Liberia. The U.S. now operates 4 mobile laboratories in Liberia as part of the American response to the Ebola epidemic. The disease has killed more than 3,400 people in West Africa, according to the World Health Organization. photo 4: Patrick Robert/Sygma/CORBIS caption: EBOLA HAEMORRAGIC FEVER EPIDEMIC IN ZAIRE. photo 5: Patrick Robert/Sygma/CORBIS caption: Pierre Formenty studies the Ebola virus in Cote d’Ivoire. Dr. Formenty was aided in his research of macaque monkeys and rats by Dr. Christophe Boesch and Dr. Bernard Le Guenno.photo 6: Patrick Robert/Sygma/CORBIS caption: EPIDEMIC STARTED BY THE EBOLA VIRUS IN ZAIRE May 14, 1995 .photo 7: John Moore/Getty Images caption: Health worker speaks to families in a classroom now used as Ebola isolation ward in Monrovia, Liberia.August 15, 2014 photo 8: Benedicte Kurzen/Noor caption: From early morning till late in the afternoon, we followed the Liberian Red Cross. They have a list of people who died and they go to their communities to collect the bodies. Every time the Red Cross workers do the same thing: they wear protective clothing, interview the family, spray the perimeter and the room, and the body. They carefully open the body bag, carry the body outside for pick up — sprayers and volunteers facing each other — and later remove their protective clothing as carefully as they can. Their work is measured, slow: any direct contact with the dead person’s body can be dangerous. In this photo, it is all about the gesture. In this chlorinated, silent corridor, there is little else that can convey humanity besides this gesture. This is one human helping another (via TIME Lightbox). photo 9: Kieran Kesner, Aug. 28, 2014. Monrovia, Liberia for The Wall Street Journal caption: This is a photograph of the first person I saw who had died from the Ebola virus in West Point, Monrovia. After the Liberian government mandated all schools be shut down in an attempt to stop the spread of the virus, the empty rooms of this school were converted into a temporary Ebola holding center. I entered the building alone and photographed the woman from a distance. I began to make my way closer to her, being careful to avoid the puddles of vomit and other pools of still liquid on the cement floor. Standing over her, I noticed the unbroken beads of sweat that remained on her face and realized the woman had only died a few hours before. I took a few steps back as a body removal team entered the room. (Via TIME Lightbox). photo 10: Jodi Bieber caption: An outbreak of the Ebola virus: A woman hands over her child to the ambulance team. The virus causes massive hemorrhaging, and is highly infectious. There is no cure, and it kills around half the people infected. photo 11: John Moore/Getty Images caption: A health worker carries Benson, 2 months, to a re-opened Ebola holding center in the West Point neighborhood on October 17, 2014 in Monrovia, Liberia. The baby, her mother and grandmother were all taken to the center after an Ebola tracing coordinator checked their temperature and found they all had fever. A family member living in the home had died only the day before from Ebola. The West Point holding center was re-opened this week with community support, two months after a mob overran the facility and looted it’s contents, many denying the presence of Ebola in their community. The World Health Organization says that more than 4,500 people have died due to the Ebola epidemic in West Africa with a 70 percent mortality rate for those infected with the virus.(photo 12: Glenna Gordon for The Wall Street Journal, Sept, 2014. Monrovia, Liberia caption: Ebola is a disease that divides husband and wife, mother and child, doctor and patient. Health care workers in protective gear that look like space suits attend to patients. Men with chlorine spray-cans take away bodies. Families aren’t given the chance to say goodbye to their loved ones. Because the virus is transmitted through touch, it overrides the basic human need for contact and connection. In this picture, health care workers hold hands and pray before doing the risky work of entering an Ebola isolation ward. They find a way to connect despite the layers of latex. No one wants to be alone when facing Ebola. I’m not a religious person. At times like this though, there’s little to do but hold hands and pray for each other. photo 13: Florence Panoussian/AFP, 2005. caption: Five health workers, dressed in head-to-toe ‘Ebola suits’ leave in a pick-up truck 09 April 2005 in Uige, about 300km north of the capital, Luanda, to collect a man dying from haemorrhagic fever. Uige, a town devastated by years of civil war is the epicentre of an outbreak of the killer Marburg virus which has claimed 180 lives so far. photo: Jodi Bieber caption: Ebola virus: The virus causes massive hemorrhaging, and is highly infectious. There is no cure, and it kills around half the people infected.photo: Daniel Berehulak for The New York Times caption: Dennis Khakie, who initially tested positive for Ebola, celebrates as he walked out of the confirmed ward after receiving a negative laboratory testing for the virus at the Bong County Ebola Treatment Unit near Gbarnga in rural Bong County, Liberia, on Oct. 4.)

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus