Notes

Downward Like a Lightning Bolt: 18 Visual Scholars Reflect on Previously Unseen JFK Assassination Photographs – #1

With the Daily Beast delivering 22 days of coverage and the traditional media flooding the web with JFK-related imagery, we at BagNews were interested in bringing a deeper visual analysis to the 50th anniversary of the Kennedy assassination. Accordingly, we invited a broad group of distinguished visual scholars to provide us with a brief response to a photograph from November 1963. The images come from this wonderful set of photographs published at the New Yorker PhotoBooth three weeks ago. The anonymous photos, drawn from an International Center for Photography archive, were published by The New Yorker for the first time. This BagNews feature is divided into three segments published on consecutive days, culminating on November 22. You can find credits for each scholar at the bottom of each post. Click on each photo for full size.

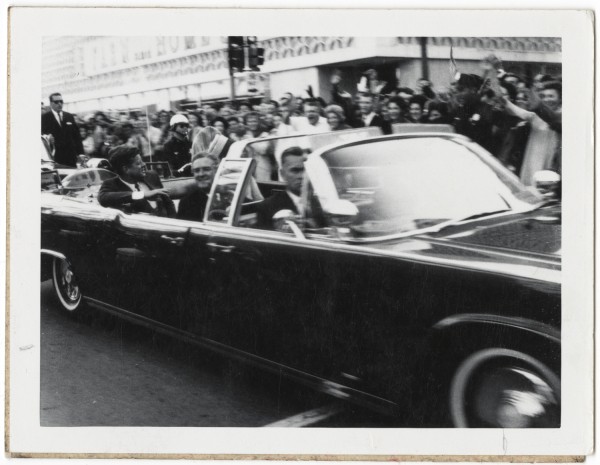

#1 John F. Kennedy. Unidentified Photographer, ca. 1963.

Ned O’Gorman

I am sure that I am not the only one to notice the eyes. “The eye is the lamp of the body,” Jesus said. Look at those eyes, for they are looking at you. Those were hungry eyes, eyes hungry to be seen, but not just to be seen but to be seen looking at the world. They were eyes that were therefore hungry for the only sort of eye that not only records and remembers what it sees, but can also be the means by which to be seen seeing. A hand is extended, but the eyes don’t see it. They look, rather, to the camera, keeping an eye on that mechanical eye, letting it see the hand that the eyes will not see. All for fear, perhaps, of not being seen looking at the world.

Michael Griffin

The introductory photograph of JFK reaching for the outstretched hand of a bystander informs with visual details more than simply prompting a characteristic impression. The disembodied bystander’s hand intrudes into the frame, and into the car in which Kennedy is sitting, in an attempt to shake the president’s hand, while other onlookers, mainly women, run in the street in the background, apparently to catch-up to the president’s car. Kennedy reaches past the most visible outstretched hand with his right arm, presumably to shake another hand beyond the left edge of the picture frame. Kennedy’s gaze, however, is not directed towards those whose hands he grasps, but instead straight into the camera to the right of the outstretched hands. The shot has stopped and blurred motion and a tilted angle evincing great spontaneity, yet Kennedy appears to self-consciously pose for the camera in a well-practiced manner. An issue that I have addressed in several essays is the distinction between the special descriptive qualities of photographs—their potential to provide unique views and details of historically specific times and places—and the ease with which they are so often appropriated as abstract and sometimes iconic symbols, becoming markers of ideological or mythic concepts that transcend the specificities of time, place, and event. The singular specificity of this photograph stands in contrast to many iconic portraits of JFK, revealing character traits, and an aura of time and place, only rarely conveyed in published news photographs.

Jens E. Kjeldsen

4600 miles away; fifty years ago. Dallas 1963. Bergen, Norway, 2013. The photographs of Kennedy in the convertible are reflections of openness and innocence. The American President is smiling. He is so close that I can almost reach out and touch him. The sun is shining – as it always did when we were children. The prints are faded, worn at the edges and slightly creased; just like the old photographs I have of myself as a child. The shots in Dallas changed the US in 1963; the shots from the Norwegian mass murderer changed Norway in 2011. The newspapers printed family photographs of the murderer as a child. Like the Kennedy photographs they carry the patina of age. The boy looked like me: Blond and smiling – a little shy.

#2 John F. Kennedy, Jacqueline Kennedy, John Connally, and Nellie Connally in Presidential limousine, Dallas. Unidentified photographer, November 22, 1963.

David Lubin

There’s everything wonderful about this photograph. Let’s start with this: that it’s fresh, we haven’t seen it before; it’s not the de rigueur Dallas motorcade shot that has been used and reused in the telling of the holy legend so often that it’s practically worthless (except to the people at Corbis). Not that this found snapshot could or should replace the professional news photo, which is now as much a part of American cultural heritage as Leutze’s depiction of Washington Crossing the Delaware—that is, a cliché that manages to stultify thought and emotion alike by its excessive compositional coherence and neatly arranged segmentation of hierarchical information about a Great Leader and his cohort at a moment of grave national significance. This photograph, paradoxically, is extraordinary by virtue of its ordinariness. Whereas Corbis gives us the equivalent of 19th-century history painting (e.g., Leutze), this picture is more on the order of 19th-century genre painting, the slightly comic depiction of everyday life.

The ghostly radio towers, to which Gov. Connolly seems to be directing the first lady’s attention, provide vertical frames within the frame. The governor’s wife is even more perfectly framed, and isolated, in the upraised side window, befitting her irrelevance to the historical drama about to unfold. The Secret Service man’s nose, elongated by the optics of motion, sprouts Pinocchio-like from his face. The president, seemingly removed from the others physically but also psychologically, leans against the car’s metallic trim, his jaw swollen in a manner strangely like that of George Washington as seen in the Gilbert Stuart portrait recreated on our dollar bills. (Washington, the legend goes, had a set of wooden dentures bulging behind his pursed lips; Kennedy, we know, took steroid medications that resulted in facial puffing.) But best of all is the creasing and folding of this much-handled snapshot, clearly one that was not locked away in a climate-controlled, high-security storage vault, untouched by human hands. Unless, that is, it’s been aged up, like an iPhone photo given the faux-vintage treatment by an instant-nostalgia app. Monochromatic in its early-60s faded Kodak blue, with the only non-blue in the field of vision belonging to the pink Chanel suit, the dog-eared and deteriorated snapshot makes strangely palpable our remoteness from that winter day.

The crease lines on the upper left of the snapshot branch downward like a lightning bolt about to strike the Leader of the Free World. The counter-branching of the blurry tree that sprouts from his head seems—only in retrospect, of course—a harbinger of the spray from his brain recorded some ten or fifteen minutes later in Zapruder’s home movie. The president’s wife and the governor look away, as if in a Renaissance painting showing the heedlessness of Christ’s disciples when the moment of passion is at hand. The semicircular crease at the bottom right seems to register an attack on the limousine, as if it had already been hit by a high-impact weapon or perhaps was being targeted by a sighting device. Either way, the photo shows the presidential barge sailing into rough waters, while the sky overhead is deceptively thin and blue. When you add to these various visual elements our knowledge of what is about to occur and our conundrum as to what really happened that day—for these too are inalienable properties of the photograph, as much a part of it now as its creased corners, dissipated blues, and blurred wintry trees—when you pull all these elements together, you have a visual text that is at once retro and prognostic, moving and banal, tragic and comic: the world’s most powerful individual is soon to be gunned down, but everything about the photo, otherwise, has a look of throw-away transience and the mundane, banana-peel slipperiness of everyday life.

#3. John F. Kennedy, Jacqueline Kennedy, John Connally, and Nellie Connally in Presidential limousine, Dallas. Unidentified photographer, November 22, 1963.

Paul Lester:

How many African Americans were on the Dallas police force in 1963? Today the percentage is about 25 percent. Fifty years ago the number was probably not that high. And yet, in the amateur photograph I chose, the racial ratio is equal—one Anglo motorcycle cop and one African American patrolman. In a still and blurred instant, Kennedy and the standing officer are forever linked by their friendly expressions toward each other that, for me, indicate mutual respect. It is a fleeting and quiet moment amid the enthusiastic cheers of well-wishers at a downtown Dallas intersection by those possibly more interested in the spectacle of the motorcade than the promise of racial equality shown by the two men.

Next Up:

Marguerite Helmers, Janis Edwards, John Murphy, Jennifer Mercieca, Karrin Anderson

See the full series here: Visual Scholars Analyze JFK Assassination Photos.

———————

Ned O’Gorman is Associate Professor, Department of Communication, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. His book dealing with the Zapruder film, provisionally titled “The Iconoclastic Imagination: Image, Catastrophe, and Economy in America since the Kennedy Assassination,” is forthcoming from University of Chicago Press.

Michael Griffin is Professor of Media & Cultural Studies, Macalester College, and Chair of the Visual Communication Studies Division, International Communication Association (ICA).

Jens E. Kjeldsen is Professor of rhetoric and visual communication at University of Bergen, Norway. He is also President of the Rhetoric Society of Europe and Editor of Scandinavian Studies in Rhetoric (2011).

David M. Lubin is Professor of Art atWake Forest University. He is the author of Shooting Kennedy: JFK and the Culture of Images (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2003).

Paul Martin Lester is Professor, Department of Communications at California State University, Fullerton and Editor, Journalism & Communication Monographs. He is the author of: On Floods and Photo Ops: How Herbert Hoover and George W. Bush Exploited Catastrophes.

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus